The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao presents Signs and Objects: Pop Art from the Guggenheim Collection, a focused exhibition sponsored by BBK that demonstrates the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation’s deep engagement with this art movement. With some 40 key works by the most significant Pop artists, the show also features a selection of contemporary pieces that explore the legacies of the movement.

Roy Lichtenstein

b. 1923, New York, d. 1997, New York

Grrrrrrrrrrr!! , 1965

Oil and Magna on canvas

172.7 × 142.6cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift of the artist 97.4565

Photo: Midge Wattles, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

© Roy Lichtenstein

© Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Encouraged by the economic vitality and burgeoning consumerist society of post–World War II America, artists such as Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, and Andy Warhol explored the visual language of popular culture—the term from which the art movement derives its name—taking inspiration from advertisements, pulp magazines, newspapers, billboards, movies, comic strips, and shop windows. The cool detachment and harsh, impersonal look of Pop art signaled a direct assault on the hallowed traditions of “high art” and the personal gesture, or free flowing brushwork, which had been championed by Abstract Expressionists of the previous generation, such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. The works in this exhibition, presented with––and sometimes transformed by––humor, wit, and irony, may be read as both an unabashed celebration of and a scathing critique of popular culture.

Originating in England in the late 1950s, the Pop art movement took hold in America after receiving support from such critics as British writer and curator Lawrence Alloway, who coined the term “Pop art” in 1958. The Guggenheim’s engagement with Pop art began early in the art movement’s development. In particular, the 1963 exhibition Six Painters and the Object —curated by Lawrence Alloway, who had joined the institution in 1961— provided institutional validation at a critical juncture. Alloway had initially considered titling this landmark show Signs and Objects, a phrase chosen for the current presentation of works from the Guggenheim collections. The Guggenheim Museum proceeded over the following decades to organize a series of important monographic surveys/exhibitions dedicated to many of the pioneers of Pop art including Chryssa (1961), Jim Dine (1999), Richard Hamilton (1963), Roy Lichtenstein (1969 and 1994), Claes Oldenburg (1995), Robert Rauschenberg (1998), and James Rosenquist (2003), while simultaneously building a collection of iconic examples of the movement that are featured in the exhibition.

In addition to historic works, the exhibition includes a selection of works by contemporary artists who explore the legacies of the movement, engaging with the forms and languages of Pop art to critique and politicize themes, particularly the language of consumerism.

Signs

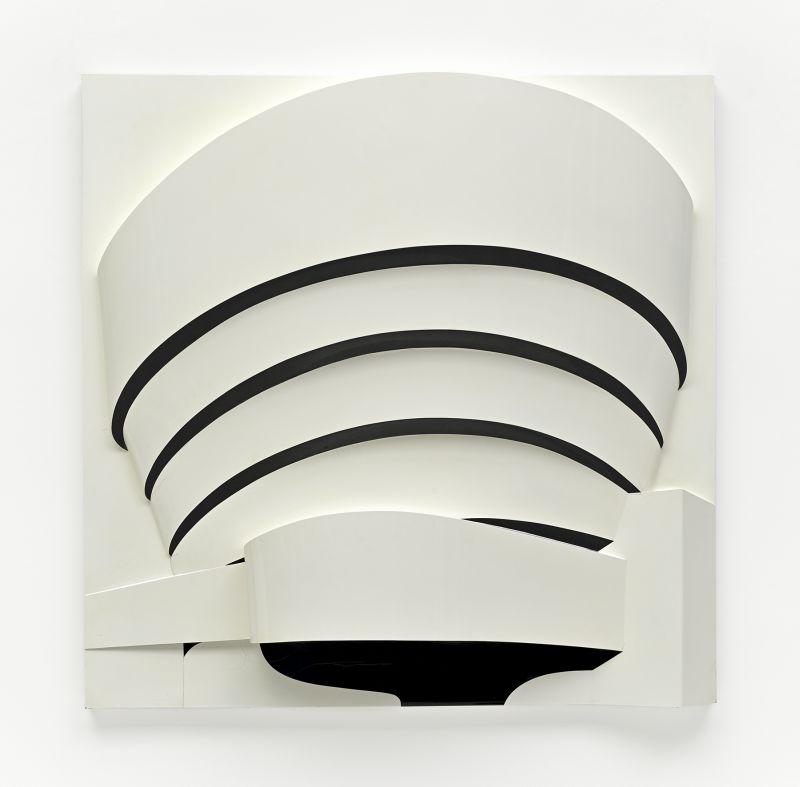

Pop artists addressed subjects that in “high art” were traditionally considered debased by incorporating the visual language of commercial culture and advertising. This embrace of so-called popular forms has been interpreted as both an exuberant affirmation of American culture and a thoughtless espousal of the “low.” Richard Hamilton is often credited as the founder of Pop art. He was a member of the Independent Group, which supported new technology and mass culture in the United Kingdom in the early to mid-1950s as a platform for creating visual art. Examples from Hamilton’s series of fiberglass reliefs of the Guggenheim Museum, which were inspired by a postcard of the landmark, demonstrate the repetition and reproduction of imagery that became a signature of Pop artists.

Richard Hamilton

b. 1922, London, d. 2011, Oxford, United Kingdom

The Solomon R. Guggenheim (Black and White) , 1965–66

Fiberglass and paint

122 × 122 × 19 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 67.1859.2

Photo: Ariel Ione William, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

© R. Hamilton. All Rights Reserved, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2024

Roy Lichtenstein painted his canvases with simulated Ben-Day dots, a direct reference to the commercial printing techniques used in comic books and newspapers. He created “high art” out of what was considered a “low,” or popular, form of visual communication taken from daily life. Following his career as a billboard painter, James Rosenquist introduced many techniques and tropes of the sign-painting trade into his artwork. He broke apart and recombined fragments of images drawn from advertising, used commercial paint, and worked on a large scale.

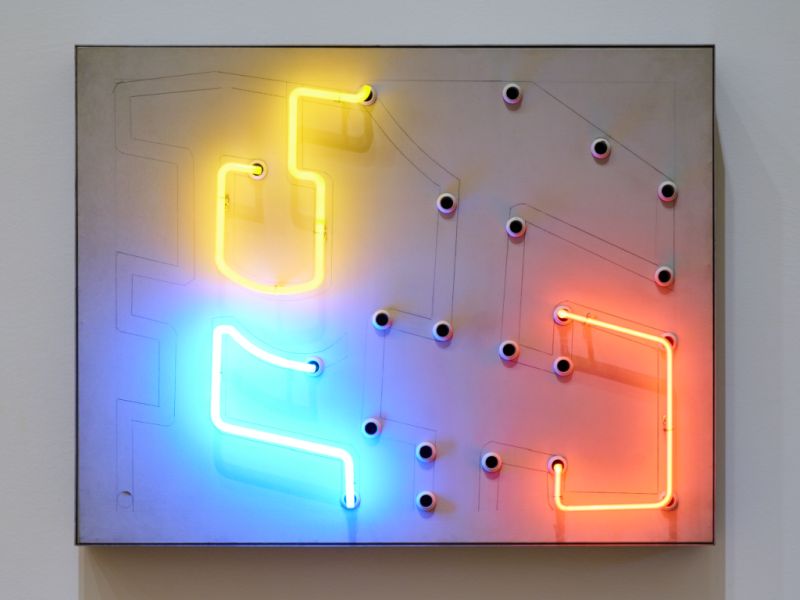

Chryssa

b. 1933, Athens, Greece, d. 2013, Athens, Greece

Construction study for That’s All , 1969–70

Neon and graphite on primed canvas over wood

96.5 × 123.2 × 20.3 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Michael Bennett 80.2720

Photo: Allison Chipak. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

© Estate of Chryssa, Bilbao, 2024

Courtesy Mihalarias Art, Athens, Greece.

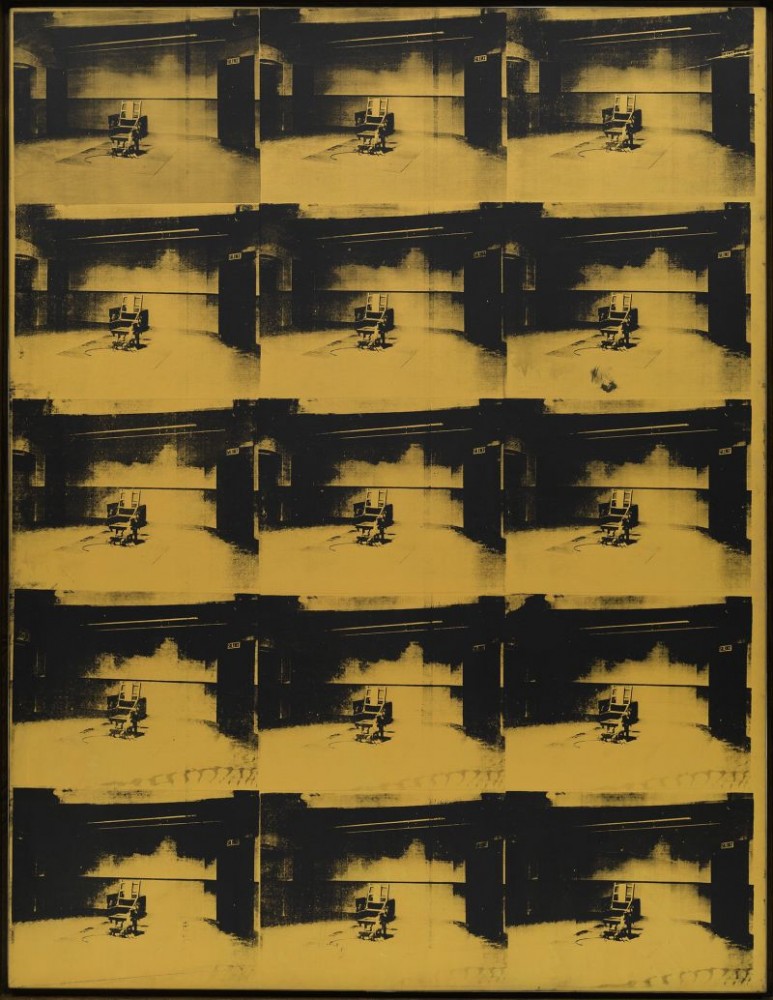

Greek-born artist Chryssa arrived in New York in the mid-1950s. She was inspired by the illuminated signs of Times Square that, for her, epitomized modernity and the entwinement of the vulgar and the poetic in U.S. culture. Andy Warhol, like other Pop artists, used as his subject matter found printed images from newspapers, publicity stills, and advertisements, among other sources. He then adopted silkscreening, a technique of mass reproduction, as his medium.

Andy Warhol

b. 1928, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, d. 1987, New York

Orange Disaster #5, 1963

Acrylic, silkscreen ink, and graphite on canvas

269.2 × 207 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Harry N. Abrams Family Collection

74.2118

Photo: Kristopher McKay, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., VEGAP, Bilbao, 2024

The relevancy of Pop has endured for generations since the 1960s. Contemporary artist Josephine Meckseper challenges the conventional interpretations of familiar images as well as the systems of circulation and display through which they acquire significance. By conflating art objects with commodities in sculptures that often adopt the form of shop displays, she draws a direct correlation to the way our consumerism impacts cultural production, often lending a critical framework to otherwise commonplace products and visuals. Douglas Gordon engages the history of Pop art by mimicking Warhol’s self-portraits and, in the case of the work on view in this gallery, directly appropriating Warhol’s film Empire (1965) by bootlegging two hours of the original cut during a screening in Berlin and then recasting it as his own contemporary artwork. Gordon acknowledges both the renowned artist’s pervasive influence and his obsessive preoccupation with celebrity and fan culture. Maurizio Cattelan also engages with familiar icons, casting the character Pinocchio from Walt Disney’s classic 1940 animated feature in a tragic tableau.

Objects

According to critic and curator Lawrence Alloway, the artists of the Pop art movement in the 1960s drew inspiration from popular culture, or “the communications network and the physical environment of the city.” Their approach to these forces and the resulting artworks are often tinged with a sense of irony. Pop artists also drew on the history of the Dada art movement in their wide-ranging practices. Like Pop art, Dada satirically incorporated everyday objects and activities as instruments of social and aesthetic critique.

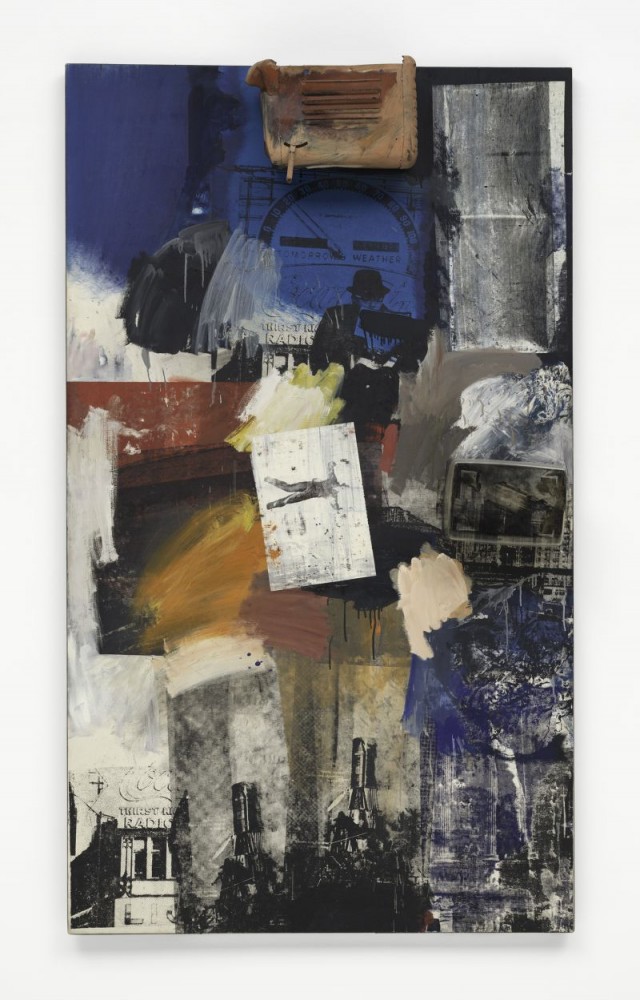

Robert Rauschenberg

b. 1925, Port Arthur, Texas, d. 2008, Captiva Island, Florida

Untitled, 1963

Oil, silkscreen ink, metal, and plastic on canvas

208.3 × 121.9 × 15.9 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Purchased with funds contributed by Elaine

and Werner Dannheisser and The Dannheisser Foundation 82.2912

Photo: by Ariel Ione Williams, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

© Estate of Robert Rauschenberg New York, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2024

A forerunner of the American Pop art movement, Robert Rauschenberg’s assemblages and paintings incorporate found objects, particularly universally available materials such as cardboard, plastics, and scrap metal, as well as mundane imagery applied by transfer techniques or commercial silkscreen processes. During the early 1960s, Jim Dine and Claes Oldenburg were part of a group of artists who extended the gestural and subjective implications of Abstract Expressionist painting into performances known as “happenings.” Combining dance, visual art, music, and poetry, these events ranged from faux dinner parties and illogical ceremonies to fictional storefronts selling absurd objects meant to critique society’s celebration of mass consumption. Later, Oldenburg created large-scale sculptures and projects (an example of which can be seen elsewhere on this floor) with the collaboration of Coosje van Bruggen, whom he married in 1977.

Niki de Saint Phalle

b. 1930, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, d. 2002, La Jolla, California

Untitled, 1979

Wax crayon, acrylic, and colored pencil on fiberglass

67.3 × 125.7 × 62.2 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Susan Morse Hilles Estate 2002.38

Photo: Ariel Ione Williams, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

© Niki Charitable art Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2024

Artists beyond Britain and the United States—Sigmar Polke from Germany, Mimmo Rotella from Italy, Niki de Saint Phalle from France, Colombian-born Miguel Ángel Cárdenas—also explored a Pop-related style, referred to in other countries as Capitalist Realism or Nouveau Réalisme, that interrogated aesthetic conventions such as the assumed originality of so-called high art.

Contemporary artists such as Jose Dávila and Lucia Hierro extend the legacy of Pop art in works that critique consumer culture, strategically incorporating Mexican and Dominican-American references that reflect their own heritage. Dávila references the stacked sculptures of Minimalist artist Donald Judd as well as Rauschenberg and Warhol’s use of common cardboard boxes and commercial packaging to create a poignant rumination on the way artworks are consumed. Hierro elevates the status of banal objects with her oversized renderings of objects commonly found in local Latin-American markets, raising issues of cultural identity, capitalism, and class.

Soft Shuttlecock

On view will also be the monumental Soft Shuttlecock (1995) by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, one of 40 large-scale projects on which they collaborated between 1976 and 2009, which was included in the opening exhibition of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in 1997.

Soft Shuttlecock was created by the artists specifically for the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed rotunda of the Guggenheim Museum in celebration of Oldenburg’s 1995 retrospective. While planning the exhibition, Oldenburg and van Bruggen were also developing a project for the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, in which four 18-foot-high shuttlecocks in plastic and aluminum were to be situated in the grass on either side of the museum, as if the building were a badminton net and the “birdies” had fallen during play. For the Guggenheim installation, the artists engaged the same object in a more whimsical rendering, this time in pliant materials. The massive size of Soft Shuttlecock humorously deflates the imposing structure of the building by diminishing its relative scale, while underscoring the museum’s institutional role as a site not only

for culture and education but also for recreation and entertainment.

• Curators: Lauren Hinkson and Joan Young, Solomon R Guggenheim Museum

• Sponsored by: BBK